The Health Care Culinary Contest is an annual competition that challenges health care culinary professionals to elevate their menus with innovative, plant-forward dishes.

The prestigious contest, now in its seventh year, is a collaborative effort between Health Care Without Harm, Practice Greenhealth, and Menus of Change – an initiative spearheaded by The Culinary Institute of America, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the College of Food Innovation & Technology at Johnson & Wales University in Rhode Island.

The competition isn't just about creating delicious food; it's about transforming health care dining with creative, flavorful plant-based options. Contestants navigate a rigorous judging process, beginning with two preliminary rounds that narrow the field to five finalists. The ultimate test comes at Johnson & Wales University's culinary program, where students and staff prepare each finalist's recipe for a panel of discerning judges who taste and score the dishes to determine a champion.

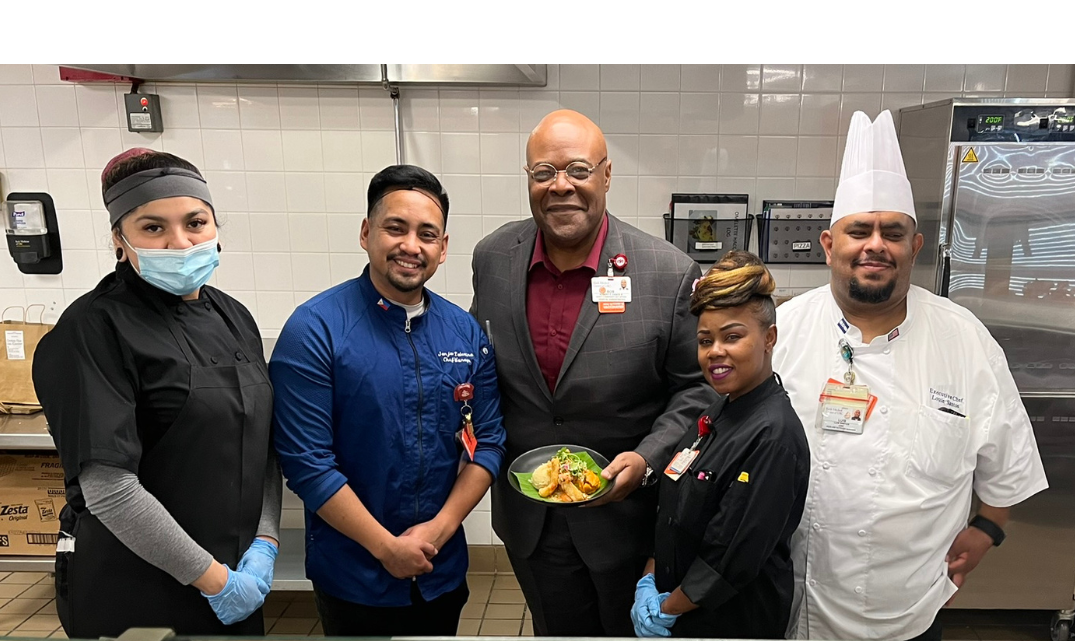

This year’s winner, Chef Luis Santos from Keck Hospital of USC, brings a unique approach to hospital food that's deeply rooted in his Honduran heritage.

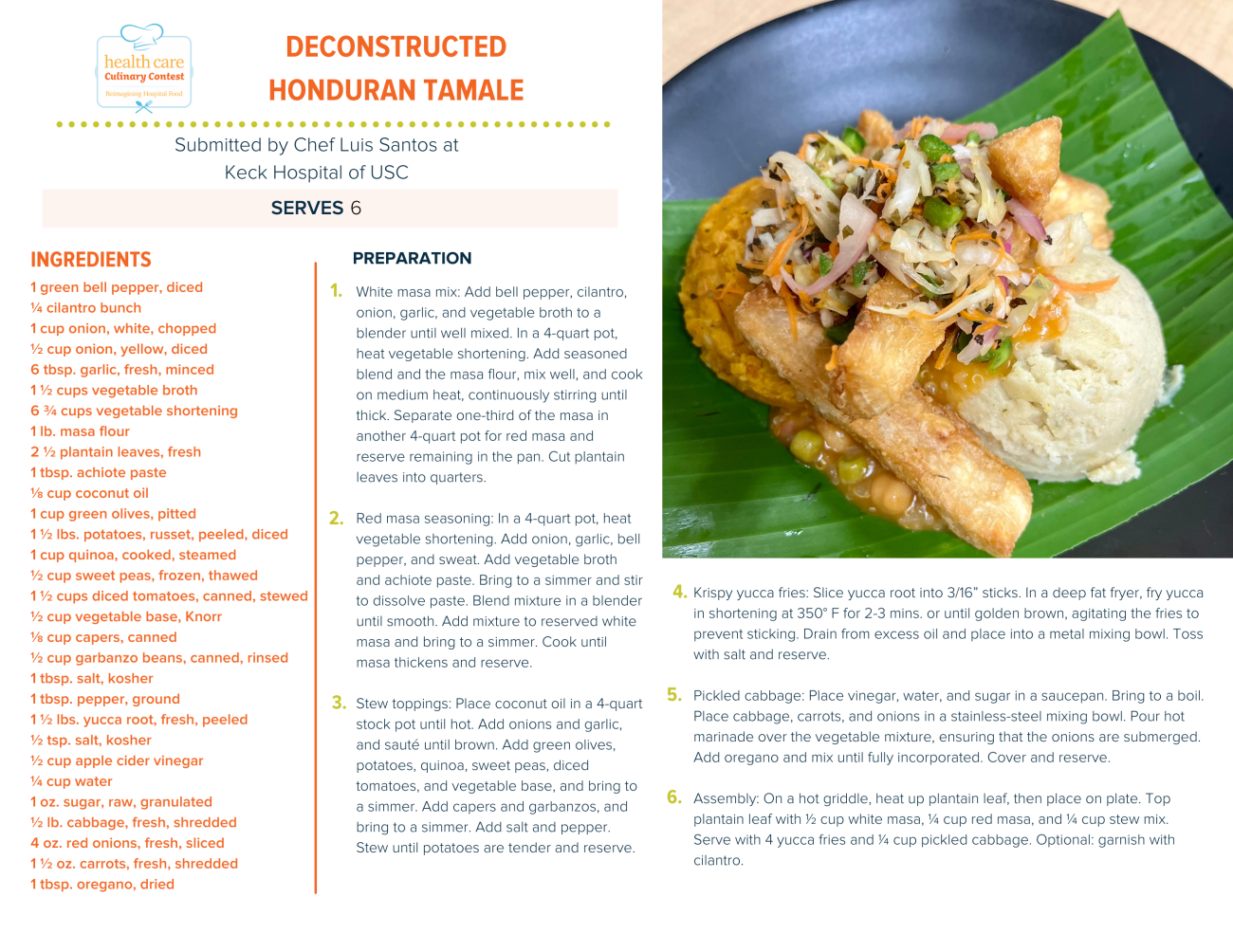

His deconstructed Honduran tamale, a plant-forward twist on a family recipe, is filled with quinoa, garbanzo beans, yuca, and olives, which replaces the traditional meat with hearty ingredients that offer the same satisfying flavors.

Santos represents a new wave of hospital chefs who see food not just as nutrition, but as comfort and healing during patients' most vulnerable moments.

He was celebrated at CleanMed May 6-8 in Atlanta, where his winning meal was served to attendees. He will also be honored at the Culinary Institute of America’s Menus of Change Leadership Summit in June. Read our interview with Santos on his win below, watch his video, and be sure to try his recipe.

Culinary roots & a full-circle journey

As executive chef at Keck Hospital, Santos oversees the preparation of more than 2,000 meals daily for both patients and retail services. He has more than a decade of experience in patient meal services across diverse health care settings.

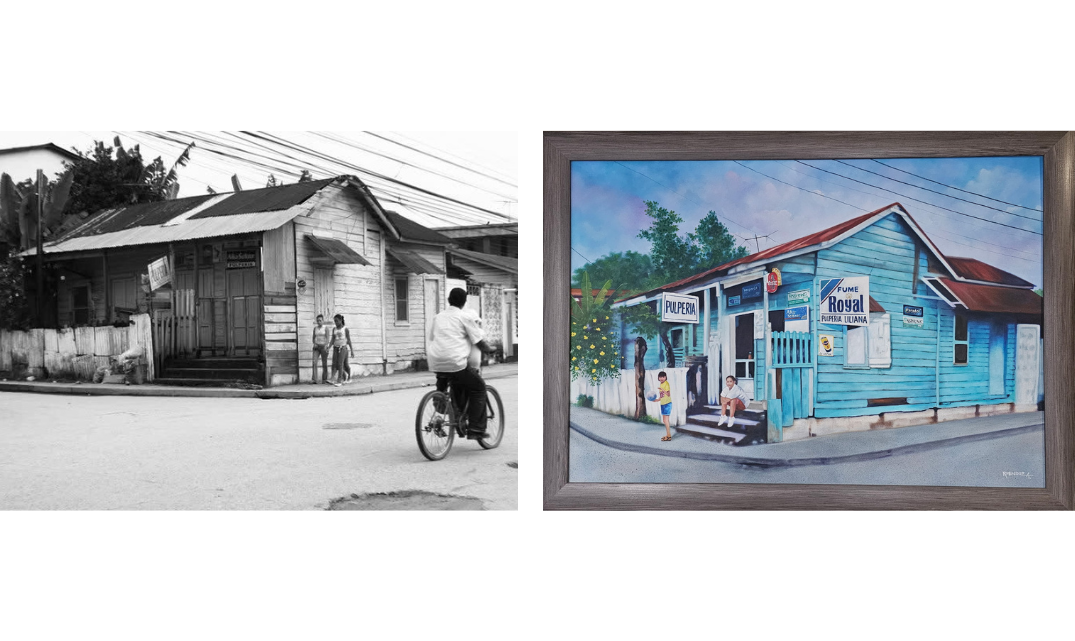

His culinary journey began in Honduras, where he spent his first seven years. There, cooking wasn't just a hobby – it was a necessity and way of life.

"Very early on, I was always in the kitchen. Being in the kitchen with my aunts was just part of my regular chores," he explains. "We used to pick our own coconuts, pick our ingredients from farms. We cooked very homestyle meals."

In a place where stores were sparse and expensive, the family would go fishing daily, preparing dishes like caracol (snail) and fish. During celebrations like Christmas, tamales were a staple that brought everyone together.

“So from very early on, I always knew I was going to be in the kitchen.”

Life took Santos to the United States, where he temporarily stepped away from cooking during his school years. However, fate would bring him back to the kitchen – and specifically to Keck Hospital.

"One of my first official jobs was here at Keck Hospital. I actually started in the dish room for about six months," Santos recalls. Under the mentorship of Chef Jose Zamora, he eventually moved into a cooking position around 2001, where he honed his skills in a high-performing, hospital kitchen environment and built his understanding of what it takes to cook for patients.

After leaving to gain experience in various establishments, including Thai restaurants, Santos found himself drawn back to hospital kitchens again and again.

"I didn't plan on being a hospital chef," he admits. "But I always came back to being in the hospital. It became my niche."

The heart of hospital cooking

When asked why he kept returning to hospital work, Santos points to both practical and philosophical reasons.

"I saw opportunities there. I saw job security," he says straightforwardly. “Some of the cooks that I knew back in 2001 are still here.” But beyond stability, he discovered something more meaningful: "Once I dove into the culinary aspect of things, I started to kind of fall in love with it."

Santos believes it takes a particular kind of person to excel in hospital cooking. Unlike restaurants, where diners come for enjoyment, hospital patients often have compromised health, altered senses from medication, and specific nutritional needs.

"You don't come to a hospital for fun," Santos reflects, quoting one of his managers. "People come to a hospital because they're visiting somebody who's sick or they’re a patient themselves. There are a couple of things that people will always remember when going into a hospital: how their nurse and medical staff treated them, and the hospital food.”

"You need to be able to read between the lines [and understand patient needs]," he explains, hearkening back to when he worked at a cancer hospital. "[For example], in a restaurant, I garnish with parsley and broccoli [but I would hesitate to do this for patients experiencing nausea] because of what they are going through. They may smell my broccoli down the hallway, so I need to watch what I serve while still being able to complete their nutritional needs."

This care and attention affect patients’ happiness and their ability to heal.

Perhaps most poignantly, Santos approaches each meal with profound consideration: "I say this a lot to my cooks, you never know when that person's last meal is – you might be serving it right now. You just gave them an awesome piece of salmon with some really beautiful vegetables, and maybe that's the last thing they experience.”

Second time’s the charm

This was actually Santos’ second time competing in the Health Care Culinary Contest. The first time occurred only days after he was hired back at Keck Hospital.

“I was still trying to learn who my staff was, how to do the scheduling, [figuring out] where do I buy my product, and 10 million other things, and then my boss comes and says, ‘There's this contest. We want to try it out.’ So, I said why not?”

While Santos wasn’t successful the first time, he built up confidence and was excited to try again. He describes how his staff, his director, his clients, and so many others had his back and supported him throughout the process. His managers, for example, helped him capture photos and video to market the recipe, post on social media, and host an exhibition station with visually appealing signs and samples.

Going into the contest this year, he challenged himself to create something that was both original to the contest and representative of his heritage. “I looked back at [the recipes from] all other winners, and I found a lot of the same things, but I didn't find anything taken from a Central American style of cooking,” he shares.

Keck Hospital honors many cultures in their menu, including Filipino, Asian Pacific Islander, and Native American cuisines. “We are very inclusive. I think I have a cultural event for every day of the week. I wanted to introduce something that we don't normally have here at Keck Hospital and bring a little bit of my Honduran culture to the people we serve.”

The winning recipe

Santos' winning dish grew from a blend of necessity, cultural pride, and innovation. His award-winning tamales represent both his cultural heritage and his ability to adapt traditional recipes to modern dietary needs.

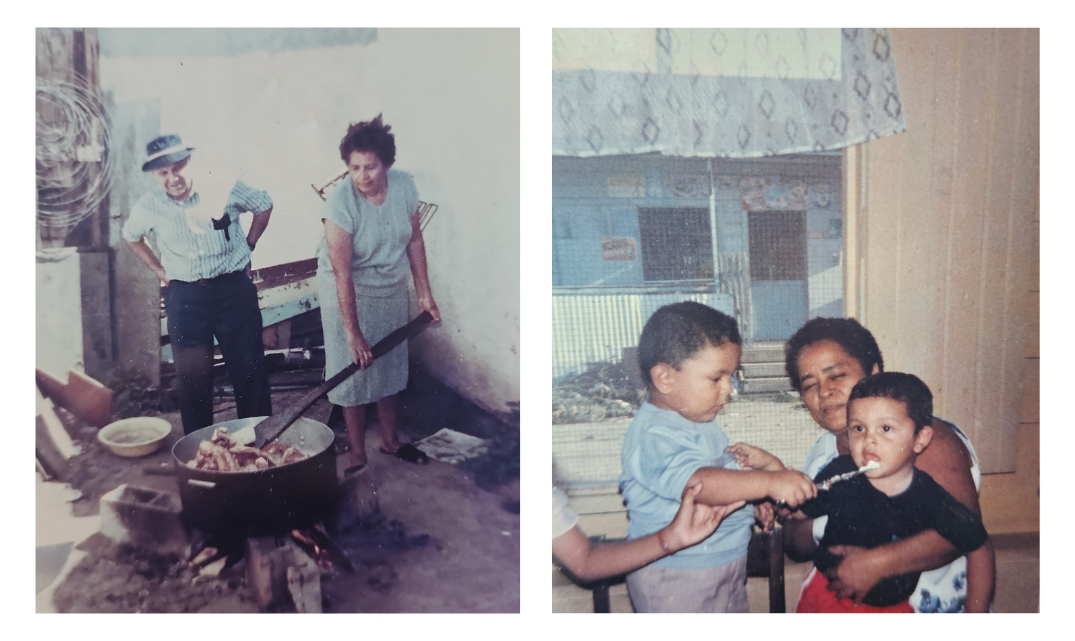

"I'm Honduran, Honduran American. Being in the kitchen with my tias, with my aunts, is something I treasure from my childhood," Santos says. He consulted with his aunts about their tamale recipe, which they have perfected making weekly for more than 15 years, both for family meals and their successful business. His recipe is a take on theirs.

“At the heart of every tamale is masa (dough made from corn flour), which carries deep cultural significance in Latinx cuisine,” Santos explains. “Masa is more than just an ingredient – it’s a symbol of family and tradition. Making masa by hand, a practice passed down through generations, is an act of connection. Corn, as a fundamental ingredient in Latinx cooking, represents our indigenous roots and cultural continuity, making it an essential part of this dish. My aunt’s expertise gave me the confidence to present a dish that uses plant-based fats that bind the masa just as well as the traditional animal fats, creating a rich, smooth texture without compromising on flavor.”

The masa is seasoned with tastes familiar to people who love Latin American cuisine, including achiote, bell peppers, garlic, and cilantro.

The plantain leaf, traditionally used to wrap tamales, also carries deep cultural meaning. “In Honduras, plantain leaves are not just functional; they are a symbol of hospitality and connection to nature. “Even though this dish is deconstructed, I still use the plantain leaf to honor its importance, serving the dish atop it to maintain that connection to tradition.”

The tamale is topped with a hearty stew of sautéed green olives, quinoa, sweet peas, diced tomatoes, garbanzo beans, and capers.

“Instead of traditional potato fries, I’ve paired this tamale with yucca fries. Yucca, also known as cassava, is a root vegetable with a lower glycemic index than potatoes, making it a better choice for heart health and blood sugar management. It’s also higher in fiber and nutrients, offering a crunchy and satisfying complement to the softness of the masa and filling.”

“To complete the dish, I serve curtido de repollo, a tangy, fermented cabbage slaw common in Central American cuisine. The vinegar in curtido balances the richness of the tamale, while the fermentation process adds probiotics, supporting gut health and digestion.”

Santos recalled how he challenged himself to create a recipe that could be scrutinized in several different ways – culturally, nutritionally, and practically. His process simplified the recipe – which is actually six different recipes – to make it accessible and replicable for other hospital chefs.

Cultural representation & reception

Santos' tamales became more than just a dish – they became a point of connection for the Honduran community at the hospital.

"I was really surprised to discover that there were many more Hondurans working here than I thought," he shares. "People would come out and say, 'You're Honduran? I'm Honduran, too!'"

These cultural connections brought both enthusiasm and scrutiny.

Transforming a traditionally pork-fat-based dish into a plant-based version wasn't without challenges. "Traditionally, masa is cooked with pork fat. So when I told them it was completely plant-based, they wouldn't believe me that it tasted correctly or similar to the way they remembered," he recalls.

"Those were my biggest critics. They’d say, 'Are you sure that masa is right? Are you sure?'" He laughs. Others questioned the presentation, as the tamales weren't wrapped in the traditional manner. He even used a different method to cook the masa, cooking it on the stovetop rather than boiling or steaming.

“I don't know if you've ever made masa, but it’s not an easy thing. Simplifying that recipe to a point where anybody could do it and all the many steps was the biggest undertaking we had to do.”

“So in a sense, I didn't think I was gonna win. People know tamales. But they don't really know Central American tamales, or Honduran tamales, for that matter."

Despite initial skepticism, the dish won people over. "We had to sell it. We really had to sell it," Santos admits. The culinary team offered samples to guests, which helped.

“The people who bought it were happy with it and actually came back and asked me for a little bit more. A few of them asked me for the recipe. So, you know, that was a big plus.”

He had a little masa left after the event, and several people came up to him and requested to take some home, recalling how good it tasted and wanting to try out his recipe themselves.

“This dish is particularly meaningful to our staff and patients because a large number are Hispanic or Latino,” he says. “Food can foster a sense of connection and healing, and I hope this dish offers a taste of home, honoring our shared cultural heritage while promoting plant-based eating for better health.”

For Santos, plant-forward means homestyle

"There's a high level of need for it. It's a more modern style of cooking," he notes, explaining his preference for working with natural ingredients like mushrooms and garbanzo beans rather than processed meat alternatives, which are high in sodium and preservatives.

He’s observed the growing popularity among guests and staff at Keck Hospital. And he says the hospital hosts two yearly events that prominently feature plant-forward dishes and promote sustainability. These events focus on composting and clean eating, and celebrate the farms and where the culinary team sources their organic products.

“A lot of people have taken to [the plant-forward] lifestyle. It's in high demand,” he shares. “It's very affordable to make. So why not do it?”

His favorite plant-forward ingredients are mushrooms and beans. He appreciates the many varieties and how universal they are to cooking styles all over the world. He loves the challenge of taking inspiration from Asian and Pacific Island, French, and Italian cuisines to find new and exciting ways to present them.

“I can make soup out of them. I can make a side dish out of them. I can put them in a sandwich. I could put them in a tortilla. Every now and then, I'll have just arroz (rice), beans, a slice of cheese, and a tortilla. [That’s the kind of meal] I grew up with.”

He goes on to describe how even when people are experiencing economic challenges, those simple, affordable ingredients can make delicious meals. And, to Santos, those homestyle meals are the essence of family and home, which is the perfect inspiration for hospital food.

Looking forward

News of his contest win caught Santos by surprise during a particularly busy week. "When the email came through, I kind of just stopped everybody. I was like, 'No way. No way!'" he recalls. The excitement spread throughout his team.

His recipe will now join the contest's collection, available to all chefs and culinary staff in Health Care Without Harm and Practice Greenhealth’s extensive network – ensuring his cultural contribution will have a lasting impact beyond Keck Hospital.

Now, Santos is incorporating the tamales into the hospital's regular rotation and already thinking about next year's contest. He's considering other Honduran specialties like baleadas – "our version of a taco with beans and avocado in a homemade tortilla" – or something with tropical coconut flavors.

For fellow chefs, particularly those in health care settings, Santos offers heartfelt advice: "You have to cook as if it were for your own family. You have to care about what you cook."

It's this philosophy – treating each meal as potentially someone's most meaningful one – that has guided Santos through his culinary journey.

“For me, being a hospital chef means being able to not just nourish people while they're healing, but maybe nourishing their souls and their energy as well,” he shares. “You ask yourself, ‘Could this be somebody's last meal?’ And when you cook with that mentality, it brings a different kind of clarity to what you're doing.”

"Care about what you do," he concludes, "because it will impact people that you may not even know."